A History of Panto

/Written by Katie Shilton

Download our PDF resource copy HERE

Many people would consider pantomime to be quite a recent invention, however it has in fact evolved into the art form it is today over the course of a few hundred years. The longevity of pantomime stems from the fact that it is everchanging, and unafraid of adapting to the fashion and tastes of the times which is why the productions we see today feel relevant, fresh and modern. Here we aim to take a look at just how pantomime as we know it came into being.

Commedia dell’arte

When looking back into the past to find the origins of pantomime most look to the Italian commedia dell’arte which originated in the sixteenth century and was a form of outdoor theatre with performers playing stock, masked characters. These performances were full of music, dance, slapstick style comedy and acrobatics, all of which are familiar aspects of today’s pantomimes.

The actors of the commedia dell’arte were given loose scripts in which the basic scenes and plot were always the same and from this they then improvised the show. All actors had a basic repertoire of phrases, speeches, jokes, declarations of love, angry tirades and so on, dependent on the type of character that they played. The nature of the commedia meant that only the most talented actors were capable of performing in it successfully. The basic plot of these productions generally revolved around two young couples, who were in love but who were constantly in danger of being separated by an old father or guardian type figure and his friend. These two old men were then constantly having their plans to separate the young lovers thwarted by two greedy, comical servants known as zannis.

Key Commedia Characters

There were many characters in commedia dell’arte. The zannis were probably the most important and it is from them we derive the word zany. There were first zannis and second zannis. The first zanni tended to be smarter and craftier whereas second zannis were less intelligent and far more physical and acrobatic. They were masked characters instantly recognisable to the audiences. Also masked were the old men characters of Pantaloon and Il Dottore.

Arlecchino as he was originally known in the Italian commedia but later known as Harlequin in French and English versions was one of the most famous of the zannis. He was the most acrobatic of the commedia characters, frequently doing cartwheels, flips and somersaults. He also had his own love interest in Columbina.

Pulchinella was another zanni, but he was characterised by malice and selfishness. His name derived from the fact that the character was pot-bellied and hunchbacked which gave him the shape like a young chicken, which is pollicino in Italian. Although he did not survive into panto many see him as the pre-cursor to Mr Punch from Punch and Judy.

Pierrot, another of the zanni, became popular in French commedia. In the French versions he was shy, naïve and sad and usually heartbroken by Columbine’s rejection of him in favour of Harlequin. He was identifiable by his white powdered face in this period rather than by a mask, a tradition still used my mime artists today. It was from this character that the clown developed.

Colombina, or Columbine, was the maid to the young female innamorati. Usually depicted as kind and clever (much like panto heroines of today), she was often also romantically linked with Harlequin. Unlike England during the 1500s in Italy women were allowed to perform on stage, as such the female roles in commedia were mostly played by women.

Pantalone was a wealthy, elderly, paranoid merchant who originated in Venice and was said to be the inspiration behind Shakespeare’s Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. Along with Il Dottore they were intended to be disliked by the audience who would delight in seeing them fooled by the zannis.

The innamorati were young lovers central to the plot. These characters had no fixed names and often there were two pairs of lovers and this led to much confusion as to who was in love with who. Again perhaps Shakespeare looked to commedia dell’arte for inspiration or the plot of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Commedia dell’arte gradually spread throughout the continent and an Italian commedia company were part of the lavish programme of entertainment that Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, put on for Queen Elizabeth when she visited Kenilworth Castle in 1575. Although it was never as popular in England as on the continent some of the characters from the commedia began to find their way in to English drama on a more regular basis from the late 1600s, probably due to their expanding popularity in France. With France being so close to England it was relatively easy for some of the performers to make their way across the channel to perform in the hugely popular English summer fairs.

With the introduction of commedia characters to the fairs in England the character of Harlequin gained increasing popularity. At this point in time Harlequin did not speak, due to restrictions on the spoken word on stage in France, but engaged in lots of energetic and entertaining dancing and tumbling which delighted English audiences.

The Creation of Pantomime

The word pantomime first appeared on a poster in England in 1717, however this was not pantomime as we know it today. The word pantomime derives from the ancient Greek where a pantomimus, the ‘imitator of all’ was a dancer who played multiple roles within the same production, expressing himself only through movement to the music and telling classic tales from mythology or the ancient writers. I think we would all agree that this bears very little relation to the productions we are all familiar with now, so how did the word pantomime come to be used for a totally different type of production?

When John Weaver produced the above mentioned ‘pantomime’ in 1717 entitled The Love of Mars and Venus, an ‘Entertainment of Dancing’ it was purely a dance show as described above. However, when a month later he produced a show called The Shipwreck; or Perseus and Andromeda which was billed as ‘A New Dramatic Entertainment of Dancing in Grotesque Characters’ he introduced the commedia characters of Harlequin and Columbine. The general public were confused by the inclusion of these characters in a classical tale and as he had previously used the word pantomime for the first production somehow this word stuck in the mind of the perplexed public and henceforward came to mean any sort of entertainment that involved these type of characters.

Although Weaver is the first to have included the Harlequin character in a production of the classical tales, it was the legendary actor-manager John Rich that really exploited this to its full potential and was instrumental in the development of pantomime.

Rich produced what is considered to be the first real pantomime in 1721 entitled The Magician; or Harlequin a Director. The character of Harlequin was transformed into a mischievous, funny magician as well remaining the love interest of Columbine. Adding the ability to do magic to the character of Harlequin gave Rich the chance to showcase his flair for spectacular. We may think of special effects being a fairly new addition to theatrical productions but in fact the early pantomimes were packed full of spectacle and were a key ingredient in their success. Under Rich sights such as working windmills and fire breathing dragons were very common. In fact so reliant were the early pantomimes on these elements that Tom Dibdin wrote “if the machinery does not work the pantomime must fail!”

These early pantomimes would probably not be recognisable to the audiences of today and were not intended to be watched by children. Originally the productions had serious and comic parts interwoven and very little linking the sections.

Following the death of Rich the form of the pantomime began to change. Although they still contained serious and comic sections these became separated into two distinct parts with the serious part being performed first and the comic part, the harlequinade, after and were linked by the fact the principal characters of the serious part were at the end transformed into the characters that would appear in the second part with a spectacular transformation scene, and this pattern endured for the next century.

It is interesting to note that the word slapstick derives from a prop from the character of Harlequin in the harlequinades. The magical Harlequin carried a sword or a bat which also acted as a magical wand and this had on it a hinged flap which made a slapping noise when he hit something or someone to give a theatrical sound in a similar way in which today we use a sound effect for falls, trips etc. It could also be used to instruct the backstage crew about scene changes.

Also in Harlequin the Sorcerer; with the loves of Pluto and Prosperine we have the first recorded ‘slosh scene’, a familiar sight in many theatre each Christmas these days which was also hugely popular with the audiences of the time.

The Rise of the Clown

Unfortunately for poor Harlequin, the late 1700s gave rise to the popularity of the clown, the most famous of these being the legendary Joseph Grimaldi who made his stage debut aged just two years and four months at Sadler’s Wells Theatre on Easter Monday 1781. His first appearance as clown however was not until 1800.

The 1806 production of Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, the Golden Egg, was the production in which the clown finally trumped Harlequin and became the central and more comic figure in the harlequinade, rather than Harlequin himself. Under Grimaldi, the clown became a mischievous, anarchic character who played tricks on people and caused general chaos upon the stage, had great acrobatic ability and was also a master of satire and comic mockery which was loved by the audiences. Harlequin was relegated once more to simply being the love interest of Columbine.

Although the clown spoke very little he performed a number of songs that were hugely popular with audiences such as ‘Hot Codlins’.

Joseph Grimaldi was so popular as a clown that another name for a clown is a ‘joey’ in his honour.

Old Stories For New

A key date in the history of pantomime is 1843 as this saw the lifting of the Theatres Act which had previously prevented any theatre without a Royal patent from producing a show with purely spoken dialogue amongst other tightly controlled restrictions. Pantomime was now free to do exactly as it pleased and it began to incorporate the witty word play, double entendre and audience participation that are so familiar to us today.

As pantomime developed through the 1800s it took much inspiration from the extravaganzas that were popular at the time, in particular those of James Robinson Planche. An extravaganza was a comic drama, full of satire and music and stunning special effects. Although this may sound similar to pantomime as it is today, at the time they were considered quite different with pantomime being considered a much coarser, lower form of entertainment. The Athenaeum in 1849 said of an extravaganza in comparison to a pantomime; “This pleasant sort of entertainment which sends light laughter round the theatre and keeps up a continual smile on the countenances of the audience, compared with the coarse exaggeration and vulgar buffoonery of pantomime, is what the raillery of polished wit in a drawing-room is to the rude horse play and ungainly gambols of rustic merry making”.

The 1700s saw a rise in the popularity of folk tales and fairy tales following the publication of Madame d’Aulony’s collection of fairy tales (a term which she originated) Les Contes des Fees in 1697, around the same time that Charles Perrault also published his collection of fairy tales, Histoires ou contes du temps Passe. The early 1800s also saw the first English translation of The Arabian Nights which contained the stories of Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sinbad. Consequently these stories began to replace the classical tales and mythology in both the extravaganzas of Planche and in pantomime.

One of the earliest recognisable titles is Mother Goose in which Joseph Grimaldi appeared in 1806, however this was a very different character and story from which we know today. Mother Goose as we know it did not truly come into being until the legendary panto dame Dan Leno played the role in a version by J. Hickory Wood and Drury Lane manager Arthur Collins in 1902.

One of our most popular pantomimes is Cinderella. Although various versions of the story had existed for a long time it became more popular when it appeared in Charles Perrault’s collection of fairy tales in in 1697. This version which introduced things such as the Fairy Godmother, the pumpkin and the glass slipper was the basis for the 1820 comic opera by Rossini, La Cenerentola, which introduced key characters to the story who appear in panto today such as the Baron and Dandini. Shortly after the opera, the tale was performed at Covent Garden at Easter for the first time as a pantomime. It was not until 1860 that the sisters of the story became ‘ugly’ and Buttons made his first appearance. Much like today the names of the Ugly Sisters were always changeable and altered to refer to topics or people that were popular at the time and the name of the Prince as Prince Charming did not become fixed until after World War One. There is also a suggestion that iconic glass slipper in Perrault’s version came about due to a mistranslation of the French word vair meaning fur for the word verre meaning glass, as in Madame d’Aulnoy’s version Cinderella’s shoes were ‘red velvet braided with pearls’. Whether it was a mistake or a deliberate change by Perrault the fact remains that today the glass slipper is one of the most iconic images in fairy tales and pantomime in the world.

Aladdin’s first appearance as a pantomime was on Boxing Day 1788 at Covent Garden and is taken from The Arabian Nights. The character of the wicked magician did not have his name fixed as Abanazar until a non-panto version in 1813, and Widow Twankey received her name in 1861 and is named after a type of Chinese green tea due the British public’s fascination with the East at this time.

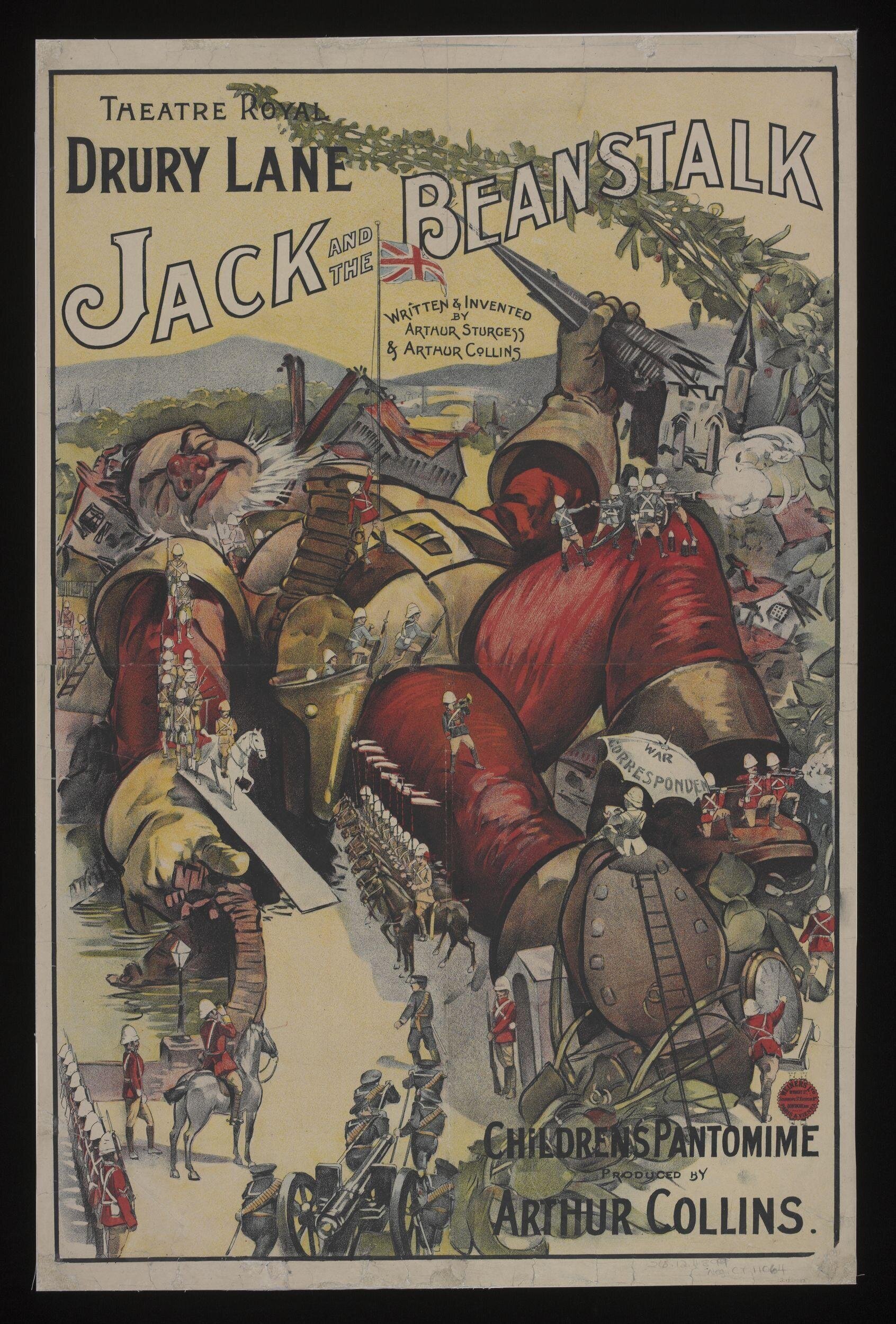

The pantomime version of Jack and the Beanstalk was first performed in 1819. The story evolved from a combination of different folk tales going backs hundreds of years. A reference to the popular Cornish folk tale of Jack the Giant Killer appears in Shakespeare’s King Lear but one of the first written versions comes from a 1734 story The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean.

The story of Dick Whittington is unusual in that it is the only one apart from the rarely performed Babes in the Wood, that is said to have its basis in fact. Indeed Richard Whittington was without doubt a real person who really did marry an Alice Fitzwarren and was mayor of London four times from 1397. Where the cat came from however is less certain but appeared in stories about Richard Whittington from 1605 onwards. As a pantomime it was first performed in 1814 as Harlequin Whittington or The Lord Mayor of London with Grimaldi as its star. It was in a 1908 production that music hall comedian Wilkie Bard introduced the song ‘She Sells Sea-Shells’, and this established the pantomime fashion of tongue twisting lyrics which is still a feature of many shows today.

From the 1860s onwards the titles of the pantomimes were pretty much fixed and the basic form has changed little since the start of the nineteenth century, however that does not mean that that the genre has not still been changing and evolving.

The Influence of the Music Hall

From the mid-1860s the stars of the music hall began to infiltrate the world of pantomime being popularised by Augustus Harris, the new manager of Drury Lane in 1880 and this influx of well-known music hall performers changed the shape of pantomime forever. Their introduction reduced the plot in favour of popular musical numbers and routines and the harlequinade became shorter and shorter until it has disappeared completely by the 1930s. Music hall stars were the celebrities of their day, much like television actors are now and so the practice of top billed celebrities appearing in panto was born. The audiences wanted to see their favourite stars performing the songs and routines that they were well known for and so scripts had to be adapted to accommodate this.

There’s Nothing Like a Dame

It was under the influence of the music hall stars that the pantomime dame began to be the star of the show. Cross dressing has been part of theatrical performances for centuries and the earliest ancestor of the pantomime dame can be traced back to the commedia and to the miracle plays of the middle ages and in Restoration comedy it was common to see men dressed as comical old women. Although Joseph Grimaldi often performed as a comical female character in his pantomimes until the turn of the century the dame role in many other productions was often small and the character not particularly interesting. One of the key figures in creating the popular character of the dame as we know it today was Dan Leno.

George Wild Galvin, better known as Dan Leno, was one of the biggest music halls stars of the 1880s. He was known for his monologues and comic songs and his characters were created from his observations on working class people in London, the most famous being his character Mrs Kelly. He played the dame at Drury Lane for sixteen year and his performance as Mother Goose strongly influenced the role of dame from then on.

There really is nothing like a dame. As characters in the commedia wore masks that were instantly recognisable to audiences who were familiar with that character, the elaborately painted face of a pantomime dame acts almost as a mask in the same way – we see a picture of a pantomime dame and even without being told we immediately know what character we are looking at.

Originally the pantomime dame could be played by either a man or a woman and the tradition of the pantomime dame being played by man was not cemented until the end of the 1800s when performers such as Dan Leno elevated the role. Interestingly today we are seeing the re-emergence of the female dame, in particular there is a small but growing trend for the Ugly Sisters to be played by females rather than males.

Principal Boys

Although women had played breeches parts for around two hundred years, this was not a device commonly employed in pantomime until the mid-1800s and this was because until the decline of the harlequinade there were no suitable roles available. However as the ‘openings’ became longer and the harlequinade shorter and roles for the popular female music hall performers needed to be found, women leapt at the chance to take on the role of the fairy-tale hero. In Victorian era England standards of propriety were so high that even the legs of a piano had to be covered. Whereas women in general were forced to wear large uncomfortable floor length dresses a woman on the stage was allowed to show her legs on the proviso she was playing a male role. This gave panto an additional appeal to anyone keen for a rare sighting of female legs!

There is much debate as to who can be classed as the first female principal boy in panto. Many would argue it was Eliza Povey in 1819 playing Jack in the first ever pantomime version of Jack and the Beanstalk who should be awarded this moniker, however she did not also play Harlequin nor would she climb the beanstalk which reached from the stage floor up to the roof. Instead a lad whose job it was to fetch water for horses at the coach station was deemed a suitable double to climb the beanstalk each night and apparently this doubling was never once spotted by the public! Because of this Madame Celeste is sometimes put forward as being the first true pantomime principal boy for her appearance as both Jack and Harlequin in Jack and the Beanstalk in 1855. However, it was really the music hall stars such as Vesta Tilley and Marie Lloyd in the 1880s that cemented the popularity of a female principal boy.

The female principal boy faced a decline in the 1950s and 60s as male stars from the music and television world started to take over the role, beginning with Norman Wisdom playing Aladdin at the London Palladium and he was followed by others such as Cliff Richard, Frankie Vaughan, Engelbert Humperdinck and Jimmy Tarbuck. This trend was reversed in the 70s when Cilla Black took to the Palladium stage as Aladdin in 1970. However, over the last two decades we have once more witnessed the decline of the female principal boy.

Skin Characters

Something once integral to a good pantomime were the skin characters. Roles such as the Goose in Mother Goose or Dick Whittington’s cat which see an actor play an animal is known as a ‘skin’ role and animal roles have been part of pantomime since the beginning. Originally any actor could be called upon to play a skin character, even Henry Irving played a wolf early in his career in Little Bo-Peep. These skin performers were once so popular it became a speciality which reached its pinnacle in the mid nineteenth century and one of the most famous skin actors was George Conquest who went far beyond the regular cow, cat and goose we think of today, once performing as an octopus in a suit that measured twenty-eight feet across. Although animals still appear in pantomime today the true specialists have almost died away as there is no longer a call for them for the rest of the year and the roles have reverted back to regular actors and members of the ensemble.

The Modern Era

Following on from empresarios such as John Rich and David Garrick, the first half of the 1900s saw Francis Laidler take on the mantle as the ‘king of pantomime’. A former clerk in the wool-trade industry Francis built the Alhambra in Bradford at the height of the popularity of the variety show which was the successor to the music hall and produced pantomime for half a century throughout the UK. His 1958/59 production of Jack and the Beanstalk with Ken Dodd was so popular it began with them celebrating Christmas and finished with them throwing out Easter eggs as it ran until March.

In the 1950s and 1960s one of the biggest names in pantomime production was Derek Salberg who oversaw numerous successful productions from the Alexandra Theatre in Birmingham. Although he employed well known people and speciality acts his pantomimes allowed the inclusion, not intrusion, of these performers, with the emphasis of the production being on its strong storyline.

The pantomimes we see today contain characters, plot devises and routines developed over a few hundred years. Some follow the model of Derek Salberg’s strong story-based pantomimes and are designed to delight and entertain all of the family, whereas others are perhaps influenced more by the music hall and variety era days in which the plot is secondary to the star turns and speciality acts and with more adult humour.

Although panto has changed considerably over the last few hundred years one thing that has not changed is its financial importance to the theatre industry and its popularity amongst the general public. Although not a fan of pantomime David Garrick came to realise as far back as 1750 just how crucial they were to the survival of the theatre industry when having resisted for as long as he could Boxing Day of that year saw him accept that he needed to give the public what they wanted and he produced his first pantomime. From this point on Drury Lane was home to one of the most spectacular pantomimes in the country with a small fortune being spent to ensure it was the best show in town each Christmas. It also helped cement the tradition of pantomimes being performed at Christmas as Garrick held the view that if he really had to do them he would associate them with the frivolity of the Christmas season, rather than with the theatre itself.

Pantomime spread outwards from London to theatres all over the United Kingdom and now almost all regional theatres have a pantomime or some sort of Christmas show playing during December. During 1900s panto gradually faded from being an offering of the major West End playhouses who instead started to house long running block-buster musicals. However, recent years have seen panto return to the West End with the annual panto at the Palladium.

Critics have been proclaiming the decline of pantomime almost since its beginning but after around 300 years it is still a major part of Christmas tradition for millions of families and brings in revenue that helps support theatres throughout the rest of the year and so to those who question whether it is dying out the answer is simple – “oh no it isn’t!” With its focus on family entertainment and ability to evolve pantomime is destined to bring magic to families throughout the United Kingdom for years to come.

Sources:

Oh Yes It Is!: A History of Pantomime by Gerald Frow

www.vam.ac.uk

www.bradfordtheatres.co.uk

www.its-behindyou.com

Photos:

Arlechino (later Harlequin) and Columbina. Masques et bouffons; comedie italienne by Maurice Sand 1862

Joseph Grimaldi. Published by Samuel De Wilde, 1807 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Dan Leno by William Davey, published by J. Beagles & Co. © National Portrait Gallery, London

John Rich as Harlequin. © Victoria and Albert Museum

Poster – Jack and the Beanstalk at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 1899 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Marie Lloyd. Photographic copy of original 19th century photograph. © Victoria and Albert Museum

Vesta Tilley – Photographic copy of original 19th century photograph. © Victoria and Albert Museum

All other images copyright Imagine Theatre Ltd